WARNING: The following post may contain technical terms that you will have to Google. If you think your computer is run by magic faeries and a pinch of gold dust, you might want to skip this one.

Console game sales far outpace sales of computer games. The Entertainment Software Association, or ESA, quotes statistics that support this claim: in 2007, console game sales accounted for $8.64 billion, while computer games accounted for a comparatively measly $910 million.

I think that there are a few reasons for this decline in PC gaming vis-à-vis console gaming. The first is that dreaded and sick thing known as "Recommended System Requirements."

I remember trying to convince my parents to let me get a console when I was 12. My main argument centered around the statement "there are no system requirements! It always runs!" This is my biggest beef with computer games, and I think it may have led to the downfall of the platform. Console games, besides the fairly obvious "this game runs on this system" sticker on the front cover, have no system requirements. It's either on such-and-such a system (and at full quality), or it's not.

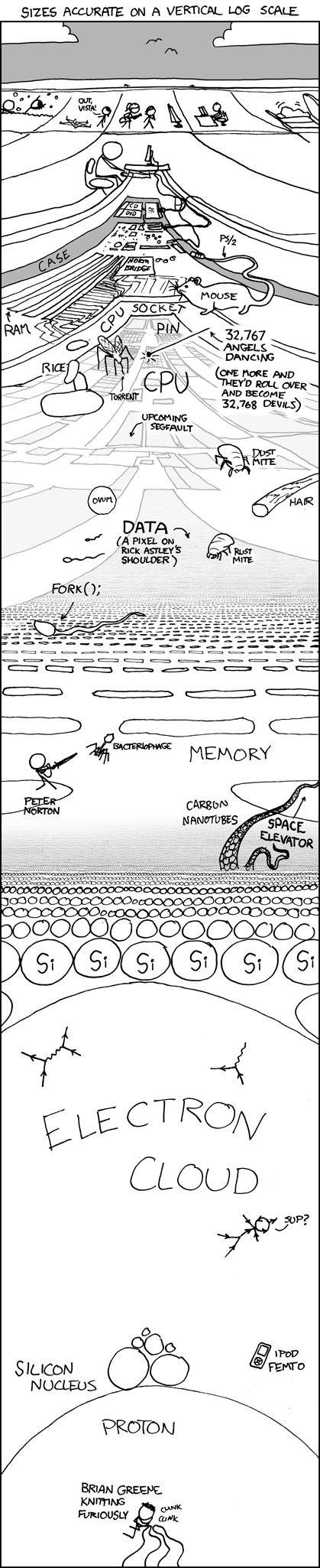

PC games, in contrast, come with a rather cryptic message on the bottom of the box that has a list of the "minimum requirements" (ie whether or not you can load the menu screen) and the "recommended requirements" (ie whether or not you can actually run the game). You have to actually know what kind of processor you have, how much RAM you have, what video card you have, and what speeds they all run at. You have to actually know how your computer works! Oh noes!

In my experience with computer games, I have bought a game, taken it home, and installed it, only to find that that it either doesn't run at all or that it runs at such low quality as to make it virtually unplayable countless times.

Console games? No problem. Go to the store, buy the game that says "I run on your console!", pop the disc in, and bingo!, you're playing within five minutes. No long installs (well, not until recently, anyway), no system requirements, no pain.

The second reason that I believe computer games are on their way out has to do with hardware. Video game consoles have pretty much the same hardware, no matter what version of a platform you buy (yes, there are occasional updates, but for the most part they consist of nothing more than a new DVD drive, or a slightly faster processor). PCs, on the other hand, are constantly being updated. New graphics cards (arguably the single most important factor in how a computer runs a game) come out almost monthly; Intel and AMD (the two major processor manufacturers) release new processors regularly; new standards of RAM (random access memory, the stuff that stores data temporarily, as opposed to the hard drive, which stores things permanently) come out yearly. The only thing that doesn't seem to change constantly in a computer is the hard drive.

Like all Apple products, PCs are obsolete almost the moment you buy them. Because of the lack of a standard of hardware - a benchmark PC - games can, and do, vary over the entire spectrum of system requirements. The prime example of this is a game called Crysis (pronounced like crisis). Gamers love to poke fun at Crysis (in the way that school kids poke fun at the bully, but are secretly afraid and awed by him). Crysis is consistently described as about two years ahead of current hardware and continues, a year after its release, to be the golden standard of extreme graphics on the PC, an amazing feat.

However, I have never seen a PC that could run Crysis at the highest settings. They do exist, but they cost $5000 and up.

Who wants to constantly have to burn money on a computer to make sure that it can run the latest games? Not I. And, it seems, not the 38% of American households that own a video games console.

The third reason that "hardcore" PC games are going to die (which finally explains the title of this post) is that the world is transitioning away from big, powerful computers to small, portable, less powerful computers. The "netbook" is a term coined fairly recently for the new category of computers with low-power processors and screens under 12" across.

I am typing this on a laptop, and although it's a huge 17" desktop replacement, the very fact that I own a laptop and not a more powerful desktop is an admission to the fact that I value portability more than power.

It is no coincidence that a "niche product" like the netbook exploded into the mainstream in the biggest year for video game console sales ever. This is the point at which computers and games go their separate ways. Video game consoles have and will continue to evolve into sophisticated multimedia centers, with games at their cores, while computers will evolve into more portable devices that center around interaction via the internet.

Indeed, some netbooks already blur the lines between the internet and a desktop environment. Google recently announced a project, called Native Client, that would run x86 code (the types of programs that you run on your computer) inside your browser, which is presently limited to things like Flash or JavaScript.

Some may argue that games like World of Warcraft, which have an exclusively PC (and Mac) audience and are extremely popular, disprove this theory. As much as I am inclined to dismiss these people as n00bs, they have a point. WoW and other Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOs) have a tremendous audience on the computer. However, new MMOs, like Bioware's the Old Republic, a Star Wars-themed MMO which has received a huge amount of hype, will be available on consoles as well as computers. As internet connection speeds increase and MMOs become more hardware-intensive, the limiting factor of the graphics of PC MMOs like WoW will cease to be connection bandwidth and will become the actual video hardware of the machines they are played on.

Computers and consoles are headed in fundamentally different directions and only one can take gaming with it. At the moment, it would appear that consoles have it mostly wrapped up. Of course, what does it matter to Microsoft and Sony, the companies that make both our computers and our consoles if we have to buy one of each?